Balcani |

The Balkan Florence Express film festival

Giulia is a blogger and she loves the Balkans. This time though she did not need to travel to much to find them. Her review of the 5th edition of the Balkan Florence Express Film Festival

(Originally published by Blocal)

I’m back in Florence for yet another edition of the excellent Balkan Florence Express , the film festival devoted to Balkan movies and organized by Cecilia Ferrara and Simone Malavolti with the help of Oxfam Italia . This year’s programme is richer than last year’s; it focuses less on the war and its consequences and more on present-day ordinary life in the Balkan countries, through different topics and cinema genres, from comedy to mockumentary.

One thing worth underlining is that, while the Yugoslav Republic has broken apart and the ghost of the war still haunts the lives of Balkan people (and –therefore- their portrayal in movies), the programme of the festival clearly shows that present-day Balkan films are co-productions and that both the cast and crew are made up of professionals from different former-Yugoslav countries, a sign that the ‘Balkan Cinema’ is still (proudly?) Yugo.

Anyway, without further ado, here are my reviews of the 5th edition of the Balkan Florence Express Film Festival.

Dubina dva (Depth two), by Ognjen Glavonic (Serbia, 2016)

Dubina Dva is the name of a top-secret Serbian plan aimed at systematically destroying some ethnic groups in former Yugoslavia. This thriller-documentary gives voice to those stories long buried in silence. The film begins when a freezer truck full of the dead bodies of Albanian civilians killed by Serbs is found in the Danube River, and this story is told through the voice of the government worker who found the truck. The film then continues with the story of Serb civilians locked inside a pizzeria in Suva Reka (Kosovo) and bombed with grenades by the local police, told through the voice of a woman who survived this genocide by pretending to be dead. The film explores how these two events are connected, with the words of the testimonies off-camera leading to the final scenes in Batajnica (an area of mass graves near Belgrade where around 1000 Albanian victims of the Kosovo War are buried) where the viewer finally connects the dots. The film is made up of a mix of spoken testimonies (both from the perpetrators and the victims) and today’s images of the places where the crimes happened. We just hear the voices over images of the grey, brute and sad landscape of cracked walls, derelict buildings and muddy, garbage-covered soil. Then, our imagination kicks in and the film begins to speak in a hypnotic way, creating images in our heads of how the events happened. Meditative, almost poetic, this documentary is a plea of guilty and an invitation to finally face up to the war crimes.

Dobra Zena (A good wife), by Mirjana Karanovic (Serbia, 2016)

Milena is a 50-year-old woman living what might look like a perfect life to the ‘average Serb’: a beautiful house, two cars, a successful husband who loves her and with whom she has a family. The awakening from this ‘dream’ comes after two dramatic events happen almost simultaneously: she is diagnosed with cancer and she finds a video of her beloved Vlada and his friends killing civilians from the time when he was in the Yugoslavian task force. And so, while politicians on TV stress the importance of giving up war criminals to the International Court of Justice in The Hague, she questions the price of her ‘perfect’ life. The cancer is a metaphor for the doubts in Milena’s mind: things she has never thought of, and which she would prefer to ignore, but which could kill her if she doesn’t deal with them –just like cancer. This movie in the first movie as a director of the well-known Balkan actress Mirjana Karanovic, who I think would be perfect in an Almodovar movie. After the screening, Mirjana discussed the movie with the audience saying that the inspiration came when she found out about a video of a military unit that had filmed their crimes in Srebrenica. This made her wonder whether she would have done the right thing or the most loyal thing to her loved ones. This is a decision that a lot of Serbs are facing right now, and Mirjana’s solution is that you can still love someone, but crimes must be punished.

My own private war , by Lidija Zelovic (Olanda, 2016)

The ‘war’ in the title refers to the raging feeling that is still inside the Bosnian people, including the author of this intimate documentary. Lidija grew up in Sarajevo and moved to the Netherlands during the war, coming back to Bosnia later on as a war correspondent for the BBC. This very personal documentary is her journey back to her family roots, an inner journey through her memory and the places and people she loves. Lidija tries to use her documentary to enable her to leave the past behind and so no longer feel like a refugee. Wanting to get closer to the truth about the war, she meets a cousin who was a sniper, a journalist friend close to Ratko Mladic, and several relatives who share their personal stories about the war with her camera, shaping this documentary from an intimate point of view.

Potop (The flood), by Jelena Jovcic (Serbia, 2016)

From a glass-like lake –which is now part of the Derdap National Park- the hotel, the hospital, the school and all the old buildings of Donji Milanovac re-emerge through the memories of its former inhabitants. Donji Milanovac was a village on the Danube River that was submerged in 1971, when Tito wanted to build a dam and a hydroelectric power station. Disconcerted, since they didn’t believe it would happen until the very last moment, thousands of people had to abandon their homes, leaving their roots in the depths of the lake, suddenly realizing that, for their State, their whole lives were just an obstacle standing in the way of progress. However, the sunken town is still alive in their dreams and memories, which are very important for the former inhabitants of Donji Milanovac, to the point that they regularly gather to double-check these memories and talk about their hometown, asking each other specific questions about the number of benches or names of the streets, because they fear that -without memories- they might forget who they are. Those little details are frozen in their minds forever, like fossils. I especially loved the story of one local who tied cans to the tops of the highest buildings to orientate himself by looking at this map of floating cans. While watching this documentary, I couldn’t help thinking that, just as these people had left their identity under the Danube, many other former-Yugoslavians had lost the place that gave them the same sense of existence under the bombings.

Eho (Echo), by Dren Zherka (Kosovo, 2016)

In this movie two stories are connected by the death of a Kosovar guy who had emigrated to Germany. Finding out about his death, a woman investigates the roots of the illegal immigrant, reaching –at the end of her journey- an old man in Kosovo. These two ageing parents, who don’t know each other and whose lives couldn’t be more different, are instead connected by their loneliness, emotions and existential conditions, those experiences –like the loss of a son- that make us equal despite the most different backgrounds. While the movie doesn’t tell us how the German lady lost her son, it’s clear that the Kosovar father lost his son twice: once after the fatal accident and, a long time before that, when his son emigrated. The movie is very slow, like the pace of the life of a parent who is apart from his son and just lives one painful day after another. All the days are similarly empty, like the houses in which they live alone.

Amok, by Vardan Tozija (Macedonia, 2016)

This was one of my favourite movies at the Balkan Florence Express Festival 2017! The ‘lost boys’ from the Juvenile Adoption Centre in the suburbs of Skopje are known for being ruthless youngsters with nothing to lose. Their destiny is already written: a life at the bottom of society, no hope in sight -as everybody keeps reminding them. One of these marginalised youngsters, Phillip, is forced by a corrupt police officer to participate in a cruel encounter gladiator-style and, after that terrifying event, his mind is broken; to put it in his words, a ‘tumour’ in his brain is devouring his sanity. And so, against a background of grey, Brutalist buildings, a leader is born. Burnt with rage, Phillip establishes a gang of fellow abandoned boys to take revenge on the world that has done them nothing but harm. This escalates into a spiral of violence through Skopje’s criminal underworld, involving all the lost boys from the foster centre. Petar, Phillip’s best friend, is the only one who has tried ‘redemption’ through a love-story, which was abruptly interrupted by the girl’s father, showing him that there is no hope for the ‘rats’ -as society calls them. The filming is rough, direct and vivid. The rhythm is tight, there is a lot of blood and violence, yet the movie is sympathetic, and its condemnation of a society that destroys those who are unable to protect themselves (actually those who should be protected by that system) is sharp and resolute. According to the director Vardan Tozija, this flaw in the system is the origin of violence, and until we are able to heal society, we won’t be able to prevent violence and rage from rising from the bottom.

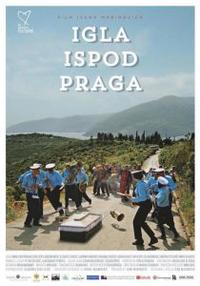

Igla ispod praga (The black pin), by Ivan Marinovic (Montenegro, 2016)

Father Peter is an obstacle to a large property sale in the beautiful Lustica peninsula. He doesn’t want to sell his plot, unlike all the other villagers, whose only chance of a decent life is selling their land to international investors who want to build a golf resort. The villagers then try incredibly creative ways of making people hate Father Peter in order to convince him to sell, from sabotaging the funeral of an old woman rumoured to be a witch to getting the priest drunk and filming him, starting off a series of comic scenes, which –however- are never reduced to the easy predictable Balkan-comedy jokes. Rather, the sharp sarcasm is based on the peculiar local mentality of this superstitious village and on the contradictions of the country. The movie also points out that Lustica is currently being destroyed by hoteliers (and the investments go through the corrupt government, enriching the political elite, although we don’t see this in the movie). I loved the gorgeous landscapes of the area, which are juxtaposed with carefully designed interior scenes, where the authentic atmosphere is built with natural light. This movie made me want to go to Montenegro before it’s too late.

Controindicazione, by Tamara von Stainer (Serbia, Montenegro, Italia, 2016)

Honestly, I don’t understand why this documentary was part of the programme. OK, the director is from Serbia, but still the story was shot in Sicily at the Barcellona Pozzo di Gotto criminal psychiatric hospital, the last OPG operating in Europe (it shut down for good just a few days ago). Nevertheless, the documentary is very interesting, especially for me: after years of explorations of abandoned mental asylums, I finally saw all those gazes and despair that I usually just imagine. The documentary is intense, somehow disturbing, and it shows the pain of the interned people, whose penalty isn’t based on the crime committed (as with detention in a normal jail), with the resulting ‘life imprisonment’ even for banal crimes. In addition to the vagueness of the penalty, we see doctors forcing the inmates to take pills and drugs against their will and without even communicating the diagnosis, nurses who couldn’t care less and actually mock the patients, and a priest who does more harm than anything (when a guy asks to talk to someone to press charges against the police officers for assaulting him, the priest replies that he can surely talk to Jesus and he will be heard, or even when someone says that the doctor physically hurt him the priest replies that he should forgive his aggressor–as Jesus teaches). The best feature of the documentary is the slapstick Via Crucis that takes place inside the hospital, whose filming spaces out the rest of the documentary, showing that the way the ‘system’ deals with the situation is even more nonsensical and delirious than the patients themselves.

Drums of resistance , by Mathieu Jouffre (Kosovo, 2016)

Before the NATO intervention in 1999, Kosovo wasn’t in the spotlight but –nevertheless- the situation was already tragic, as the Serbian regime had banned Kosovar Albanians from participating in public life. In this documentary, the little-known story of Kosovar Albanians during the 1990s is told by people conversing: while drinking and chatting around two different tables, both the younger and the elder groups of dining companions share their vivid memories and –ultimately- a very intimate view on one of the most tragic periods in the history of Kosovo, providing a complex picture of Prihistina. At that time, Albanian public employees were fired and students were banned from schools and university, so teaching happened in private apartments and shop basements. In this apartheid scenario, a whole parallel society was organized, which was a non-violent resistance to the oppressive regime. The story is spaced out by scenes of the contemporary composer Liburn Jupolli who plays either guitar or drums, like a punk minstrel.

Krom (Chromium), by Bujar Alimani (Albania, 2015)

What I liked most about this movie is the background of beautiful rural Albania, especially the quiet lake. It is also the favourite spot of the protagonist of this coming-of-age story, Adi, a teenager suffering for his mute and lonely mother. Wishing to prove his independence, Adi quits school and begins working illegally at the local mine, until he is uncovered by his teacher, a rock lover who -in turn- has risen up against her parents (I love the Albanian rock music that she listens to in the car!) and the only person who shows that she cares about Adi. The pace of the movie is slow, and the narration is poetic and evocative: every expression or inner thought is way more important than a dialogue. Chromium is not only the mineral that Adi extracts from the mine, but also a metaphor for something dark that actually hides gold, like the souls of these characters, which are lit from within.

Preludijum za Snajiperu (Prelude to Sniper), by Danilo Marunovic (Montenegro, 2015)

This is a documentary movie on the eminent Montenegrin sculptor and painter Dimitrije Popovic, known for working on several contemporary topics such as terrorism, consumerism and exploitation of the female body, but mostly for interpreting Biblical motifs in a universal, contemporary language, often dotted with erotic symbolism. The ‘erotic power’ of this movie is represented by Severina Vuckovic, the biggest pop-folk star in the Balkans, who began her career as a porno-star and now, for Popovic, interprets the Biblical princess Salomè. The sniper of the title comes from an artwork by Popovic exhibited in Paris, and which inspired the director to make the documentary. It represents the dialogue between a gun and a piano, thus the duality of destruction and creativity. The idea of the sniper is further fitting, as Popovic’s artistic ideas are as real, sharp and accurate as a sniper’s shot.

Smrt u Sarajevu (Death in Sarajevo), by Danis Tanovic (Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2016)

This was my favourite movie at the Balkan Florence Express Festival 2017! From the Oscar-winning Bosnian director Danis Tanovic (No Man’s Land, 2001), this choral drama summarizing Bosnia’s paralyzing discord was welcomed in Florence by a throng of fans. The story is inspired by a monologue written by the French philosopher Bernard-Henry Lévy, which is transposed into this movie through the speech that a French actor is researching in his hotel room, since he was going to be the main lecturer at a conference to take place at Hotel Europa on the 100th anniversary of the assassination of the Archduke Franz Ferdinand by Gavrilo Princip. The whole movie is shot inside this iconic hotel, where the preparations for the big event are in full flow. The financial situation of the hotel isn’t good and its employees, who haven’t been paid for two months, are planning a strike on the evening of the big event. In the hotel basement, a suited pimp rules over his own kingdom of gambling and pole-dancers, while another key character of the movie is a coked-up security guard who is responsible for the safety of the French VIP guest. On the rooftop, a television troupe is shooting a series of interviews presenting different point of views on the controversial figure of Gavrilo Princip, a dispute that is still very hot in Bosnia: Serbs consider him a hero, while Muslims see Gavrilo as a terrorist. Meanwhile, the French spokesman is in his room researching the commemorative speech, which follows the exact words of Bernard-Henry Lévy’s ‘Hotel Europa’, even if the director decontextualizes it. And so the speech appears as totally outside the real world, a real world where dozens of employees are on strike inside the very same hotel (which is going bankrupt as a consequence of the contemporary economic crisis) and –yet- the political commentary goes on rambling about the role of Sarajevo in the 20th century. The point is that, once again, Western countries fail to understand Sarajevo’s issues while they are happening, but are good only at timeworn rhetorical speeches. My favourite character was the manager of the hotel, Omer, who crosses all layers of the story (symbolically represented by the different floors of the hotel) but he doesn’t belong to any of them, and whose progressive and ineluctable downfall represents Bosnia’s defeat in its cycle of negative events –from the assassination of the Archduke to the present-day economic crisis. In this way, the hotel is a metaphor for the whole country, inhabited by different people and criss-crossed by different stories: a microcosm of conflicts, divisions, wars, rivalry, violence and abuse of power, and the plot itself is a multi-levelled allegory for modern Europe, where past and present are inextricably intertwined, unavoidably passing through Sarajevo.

S one strane (On the other side), by Zrinko Ogresta (Croatia, 2016)

This movie is about the political and social consequences of the war, but also about human complexity and irrational feelings. It’s an engaging psychological thriller dealing with the life of the family of a former commander of the Yugoslav Army that, after being in the spotlight during the trials at The Hague, is forced to move from Belgrade to Zagreb and hide their identities. Here, after 20 years of silence, Vesna receives a heartrending phone call from her husband who, as a ghost from the past, is back in the life of his family bringing with him tragic war secrets. This is a movie about forgiveness, where the story is told through personal emotions and points of view, with the result that the components of the JNA aren’t just the leaders of the Yugoslav army, but also husbands and fathers. This movie is fast-paced, with the rhythm of a thriller and an unexpected twist at the end showing that –after the traumatic events of the war in Yugoslavia- someone is still waiting for their revenge, although it’s clear that the revenge can’t erase the pain suffered in the past but only spawn more pain and guilt.

Zivot je truba (Life is a trumpet), by Antonio Nuic (Croatia, 2016)

Yet another movie I liked a lot out from the programme of the Balkan Florence Express 2017! This movie is unpretentious and –because of this- brilliant and fun. What is mainstream everywhere else -a Christmas family comedy- is actually a niche in the Balkans, where the majority of movies are still about the war and its tragic consequences. In this sense, this film is uncommon and unconventional, since it deals with the adventures of Bura, a just-married trumpet player waiting for his first son, and his family, who own a slaughterhouse oppressed by a debt, against the background of present-day Zagreb. I especially loved the ‘urban style’ of the movie made up of a series of scenes recalling music video clips of Bura crossing the city by bike on the best jazz-fusion soundtrack ever.

Soul train, by Nermin Hamzagic (Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2015)

Five popular Bosnian rappers travel on a train-turned-recording-studio to discover the different musical traditions of their country, from the still-surviving choirs established by Tito as a mandatory recreational activity to the traditional sound of sevdah, here interpreted by the amazing singer Bozo Vreco. In Sarajevo, the leading rapper performs with the philharmonic orchestra, and the result is stunning! Political issues of modern and contemporary Bosnia are never addressed directly, but constantly surface from the dialogues and the debate between different musical traditions, different generations and different regions of the country. I liked it because it shows a side of Bosnia that isn’t shown very often in films, although it’s disappointing that the outcome of this experiment, the fusion tracks recorded on the train, aren’t part of the soundtrack of the movie.

Huston, imamo problem (Huston, we have a problem), by Ziga Virc (Slovenia, 2016)

Simply brilliant! This mockumentary (that is, a fake documentary) tells the story of the advanced space programme that Tito supposedly sold to Kennedy, a conspiracy theory -which was pretty popular in Yugoslavia- justifying the role of the States in the war of the 1990s. The movie is built up through the ‘creative editing’ of archive footage juxtaposed with se