Open Balkan, closed doors: unveiling women’s limited opportunities

Despite the aspirations of the Open Balkan initiative to foster regional cooperation and economic integration, women continue to encounter barriers in accessing meaningful employment opportunities

Open-Balkan-closed-doors-unveiling-women-s-limited-opportunities

Belgrade, Serbia, waiters during a break - © Shutterstock

Zlatka*, a 30-year-old economist from Kavadarci, in North Macedonia, intrigued by the Open Balkan initiative, decided to seek a new job in Serbia. Dissatisfied with her employer at the time and lack of career progression opportunities, she saw the initiative as a chance to prove herself abroad, improve professionally, and potentially relocate her entire family – husband and two young children – to a place with better prospects.

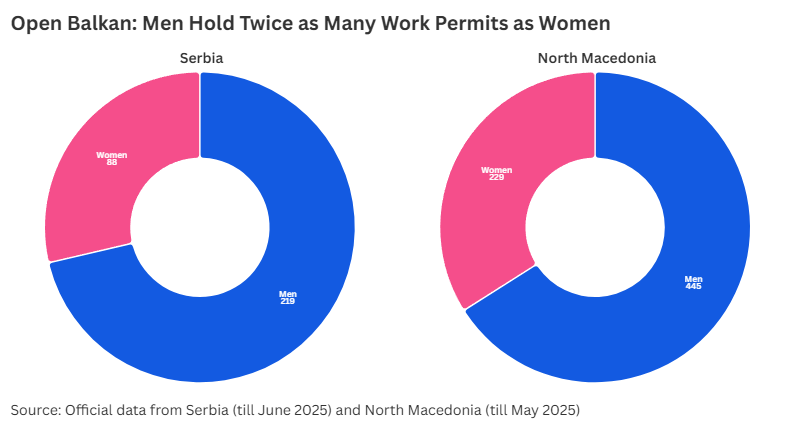

Zlatka is one of 88 women from North Macedonia who have applied for a work permit in the neighbouring country, Serbia, since the beginning of the Open Balkan initiative for free access to the labour market in March 2024 to date. The other 219 were men, all from North Macedonia except one from Albania.

It was December 2021 when leaders from these three countries signed an agreement for free access to the labour market in the Western Balkans. A few years later, despite being highly promoted, this initiative has not had the expected and widely anticipated impact on the region, especially for women. Official data from Serbia and North Macedonia show that around 30 per cent of work permits have been issued to female workers. In the case of Albania, no data were available to be shared or publicly disclosed, despite multiple requests.

“I believe the main reason for the significantly higher number of men among foreign workers lies on the demand side – employers are seeking foreign labor for jobs traditionally seen as male, such as construction or transport”, says Sarita Bradaš, psychologist and labour law expert. “The second reason is rooted in traditional gender roles. Men are expected to be the providers, hence they are more motivated to seek work abroad. Women are expected to care for children and households, which limits their ability to migrate”.

Speaking about the labour market, Bradaš warns that “women in Serbia are already in a bad position and the situation for foreign women is even worse”.

Data show that the situation is similar in North Macedonia, with a total of 675 work permits issued via the Open Balkan mechanism, of which 445 to men from Serbia, 229 to women from Serbia, and one to a man from Albania.

Facing the obstacles: the promised road without a hope

“The contracting countries committed to simplifying administrative procedures for entry, movement, residence and work of nationals from other contracting parties. They also committed to guaranteeing equal access to the labour market in the host country for nationals of other cotracting parties, in accordance with the agreement and national legislation”, reads the response from the Serbian National Employment Agency. They also claim that the Open Balkan initiative is equally aimed at both sexes.

“Whether and how someone will use the benefits offered by the labor market depends on several factors. On the one hand, there are market conditions and the demand of employers for certain profiles, and on the other, the level and type of qualification that the person possesses”, they wrote in their official comment regarding female presence. “Also, we must not forget the personal characteristics, such as the expectations of the persons themselves and their often expressed desire to work primarily in the field for which they were educated and trained”, they stated.

The system operates as follows: citizens of three countries can apply using their electronic ID via e-government platforms to obtain an Open Balkan identification number, which they can then use to access job applications on platforms in the other two countries.

For Zlatka from North Macedonia, the first steps were easy: she used the Open Balkan platform, applied for several jobs in Belgrade, and soon received an invitation to an interview. She felt hopeful and fulfilled – but only briefly. Disillusionment followed during the permit and residence procedures.

The first hurdle: when one family member gets approved for labour market access, other family members do not automatically receive residence or work rights. They must regulate their status separately, under national law.

Despite the Open Balkan’s promise of easier labour market access, she faced numerous barriers, including administrative procedures, recognition of qualifications, cultural differences, limited access to public services, and housing challenges. These obstacles ultimately made her give up on the idea of moving abroad to build a better future elsewhere.

The experience of Uendi Ramaj, an Albanian student at the University of Belgrade, illustrates further problems and obstacles. After receiving a scholarship from the Serbian Ministry of Education and actively engaging in regional academic activities, she applied through the Open Balkan digital platform in February 2024 for access to the Serbian labour market.

More than six months later, she had received no response. “Everything was supposed to be digitally ready”, explains Uendi. “But I never got a confirmation. No one has been able to tell me what went wrong”. She contacted officials in Albania, only to find that they were totally unaware of the procedures.

“In my hometown, some civil servants did not even believe the programme existed. I ended up having to teach them how to navigate the platform”, says Uendi. “They should also consider that still many people who are not emigrating due to lack of skills do not even know they have the right to apply”.

Even those with digital access and education struggle to navigate the opaque bureaucracy.

“If this is how it works for someone like me”, says Uendi, “I cannot even imagine how difficult it is for women who do not have time and support or access to information”.

As of mid-2025, there is no open data on the number of people who have successfully accessed employment through the Open Balkan ID system. In particular, considering that female unemployment in the region remains disproportionately high, the lack of transparency and the absence of targeted outreach mechanisms further marginalise women, especially those already facing limited digital access and heavy caregiving responsibilities, by restricting their access to information, opportunities and decision-making.

“Many young women I know did not even try”, explains Uendi. “They had not even heard about it. Thus, the information is not reaching the people who would benefit most”. She is now considering applying for a master’s programme under the Erasmus Mundus scheme or other similar opportunities. The already tested European mechanisms can be perceived as more reliable than those promoted within the region. “It is hard to trust the system when it fails you at every step for reasons that are never clearly explained”.

Fitore Ademi, a young Albanian of Kosovar origin, had a similar experience within the Open Balkan initiative. She participated in a youth cooperation programme that included work in Albania, North Macedonia and Serbia. “There were three organisations, different working groups and we were supposed to spend time in each country”, explains Ademi. “Our group worked on the production of a policy paper on the brain drain of young people from the region. We had strong theoretical support, including mentoring and research”.

However, when it came time to travel to Serbia in June 2024, Fitore reported that she was denied entry despite having a valid passport. “It did not matter if I used my ID or passport. They just refused me at the border. The programme managers could not help at all. I had to return to Kosovo and then to Albania. I never got an explanation. The issue was never resolved”.

Although active in youth organisations and eager to contribute fully and commit herself to the programme’s participation, she was effectively excluded from the programme’s practical activities. “These programmes should help us overcome divisions and build cooperation. They help develop soft skills and trust. But when even institutional programmes fail, the result is disillusionment”.

Fitore’s conclusion is shared by many in her generation and much beyond. “At this point, I think it would be better for us to invest time and money in visa applications to leave the region entirely. This now seems to be the only valid option”.

Was the Open Balkan made to fail?

“Open Balkan is a completely misguided initiative. Serbia is not an attractive labour destination because it does not offer decent work conditions, and this is evident from the number of work permits issued”, believes Sarita Bradaš.

The data that emerged from the research are not surprising, agrees Belgrade-based jurist Mario Reljanović, specialised in labour law. “It is good that some administrative barriers were removed for citizens of the three countries, but when it comes to a unified labour market, it never truly had strong prospects”, explains the jurist.

Reljanović sees two key obstacles that limit the project’s appeal. “First, existing labour migration patterns show low interest in cross-border movement within these three countries. While some workers came from North Macedonia and Albania to Serbia, the number is were small”.

According to the jurist, workers leaving their home countries look for destinations with significantly better labour market which is not the case for any of these three.

“Even if Serbia offers slightly higher wages, it is not enough to choose Serbia over EU countries – argues Reljanović – the cost of living often cancels out those gains. Working conditions are poor in all three countries, arguably worse in Serbia in normative terms, even though the practical problems are similar”.

“Second, many migrants prefer countries with established diaspora communities from their region, including second and third generations, which reinforces migration patterns toward Western Europe”.

It is unclear whether the initiative is still in place, as platforms are often unresponsive, multilingual support is lacking, and frontline staff is uninformed. The initiative has failed to account for the realities many women face. The lack of gender-sensitive design and the absence of reliable data make it extremely difficult, if not impossible, to establish whether women are benefiting at all.

*Some of the names in this article have been changed at the request of the interviewees

This publication has been produced within the Collaborative and Investigative Journalism Initiative (CIJI ), a project co-funded by the European Commission. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of Osservatorio Balcani Caucaso Transeuropa and do not reflect the views of the European Union. Go to the project page