Ned, the silk merchant’s son

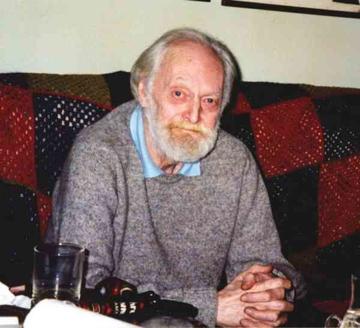

On the occasion of the twenty-fifth anniversary of the death of Professor Edward Dennis “Ned” Goy (1926–2000), a look at the life and cultural activity of this great Slavic scholar and translator of important works by Serbian and Croatian authors

Ned-the-silk-merchant-s-son

Vintage old hardback books, fanned pages on wooden desk table. © 83054/Shutterstock

The news of the death of Professor Edward Dennis “Ned” Goy, which occurred on 13 March, 2000, along with various in-depth articles on his life and work, was published by all the major English newspapers, including The Independent, The Daily Telegraph, The Guardian and The Times. These were also joined by several Croatian and Serbian newspapers, obviously reflecting the rigid post-war divisions, and therefore without mentioning Ned’s translations and academic articles on the literature of the “opposing” camp.

In one of his texts, Professor Dušan Puvačić , a London friend of the great Slavic scholar, calls Ned “a pioneer of South Slav studies in England”, “a true scholar, an authentic critic”. Puvačić emphasises that Goy had enthusiastically welcomed the news that in 1999, almost simultaneously, the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts and the Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts had nominated him as a “foreign” member. However, Goy died before these awards were officially confirmed.

“It is difficult to find a better example of moral integrity and intellectual honesty than this man who always modestly considered himself ‘a simple foreign expert in South Slavic studies’”, argues Puvačić.

Despite his “simplicity”, Ned Goy struggled to accept the dissolution of Yugoslavia, yet he demonstrated courage in expressing his position, for example on the NATO bombing of Serbia in 1999, as well as a subtle touch of irony. When journalists asked him what he thought of what was happening in Sarajevo, Ned replied that he would speak to them if they pronounced the city’s name correctly. I imagine the journalists walked away from him thinking: “How eccentric!”, perhaps even incredulously: “He could have appeared in the media, and he did not want to hear about it?!”.

Only a man of such character could decide to study Russian in high school during World War II.

Now let’s learn something about the life and academic career of Ned Goy, a Slavic scholar and translator who for decades had been working diligently in two linguistic mines (indeed, true translators are miners of both their own language and that of “others”). Forgive my digression: translators are rarely, if ever, invited to public presentations of translated works, and not only in Italy. Often, their names are not even mentioned in reviews.

Ned Goy was born on 22 September, 1926, in Enfield, Middlesex. His father, Edward Smith Goy, was a silk merchant in London, and his mother, Elizabeth Maud Dennis, was a seamstress – a creative and determined woman from a mining family. (The surname Goy derives from an old French term for a type of hook used by winemakers and coopers, suggesting a Huguenot ancestry.)

He grew up in Petersfield, Hampshire, and later described having a happy childhood, marked by his love of nature and his passion for fishing. He lost his father at the age of eighteen. He was attending Churcher’s College in Petersfield.

His family was not wealthy, so he was forced to work as a teacher in private schools to complete his education. Shortly before graduating, he began studying Russian. After being mobilised in 1945, he was sent to Cambridge for a Russian language course organised by the army. He later served as an interpreter for the British mission in Poland and Germany. According to some accounts, he loved military life, especially the discipline.

After leaving the army in 1948, he enrolled at Queen’s College, Cambridge, where Slavic scholar Elizabeth Hill suggested he study Serbo-Croatian in addition to Russian. His first Serbo-Croatian teacher was Miodrag Stajić, replaced in 1948 by the former Dalmatian bishop Irinej Đorđević. For the young English atheist, the encounter with the Orthodox priest proved to be of extraordinary intellectual significance.

By “reviving” the Serbian language and literature in the eyes of the young Slavic scholar, Đorđević managed to direct him towards that “Balkan cauldron” to which Goy would remain tied for the rest of his life.

After graduating in 1951 with a degree in Russian and Serbo-Croatian language and literature, he decided to move to Belgrade to gather material for his doctoral thesis entitled “Russophilia among the Serbs and the Penetration of Russian Literature and Thought in Serbia”, which he defended in 1954.

From then until 1990, he taught primarily Serbian and Croatian Slavic studies at Cambridge. He published numerous excellent essays on Russian literature, but increasingly focused on the Serbo-Croatian language, becoming one of the leading experts in the West. He is the author of many essays and books of great importance to generations of students of the Serbian and Croatian languages. He then turned to translation, striving to introduce Serbian and Croatian literature to a wider audience. One of his finest works is the translation of Petar Hektorović’s Ribanje i ribarsko prigovaranje[Fishing and Fishermen’s Talk], a narrative poem from 16th-century Croatian literature. Goy was particularly enthusiastic in identifying the names of all the fish.

In Yugoslavia, especially in Belgrade and Zagreb, he made friends with many writers, as evidenced by his correspondence, partly published. He maintained an intense correspondence with the writers whose works he translated: Miodrag Bulatović, Vladan Desnica, Radomir Konstantinović, Dragutin Tadijanović…

“Although he seemed somewhat of a loner among his colleagues (his approach to textual analysis, partly inspired by the works of F.R. Leavis, was atypical and often viewed with scepticism by Slavic scholars), he was an imaginative teacher, known for his original and lively lectures based on immense knowledge”, recalls Puvačić and points out: “In interpersonal relationships, he often adopted a provocative stance to stimulate discussion, sometimes even causing confusion among students, who, however, never questioned his good intentions”.

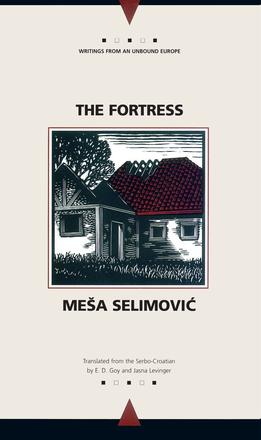

Puvačić goes on to describe Goy as a warm, devoted, passionate husband, faithful to his two wives, who died prematurely. But it was only when he met Jasna Levinger, a linguist from Sarajevo, twenty years his junior (daughter of economist Mirko Levinger), that Goy found his true soul mate. “They married on 7 February,1997, embarking together on one of the happiest and most productive periods of their lives, translating works of Serbian and Croatian literature. Together, they completed the translation of Meša Selimović’s novel Tvrđava [The Fortress] (1999) and Banket u Blitvi[The Banquet in Blitva] by Miroslav Krleža (published in 2001). However, shortly after he began work on a translation of Roman o Londonu [A Novel of London] by Miloš Crnjanski, Goy suddenly collapsed, dying four hours later, on 13 March 2000, at Addenbrooke’s Hospital in Cambridge […] An extraordinary academic, a brilliant and innovative professor and an independent thinker, Goy is remembered by his students and friends first and foremost as a humble, witty and benevolent man”.

My first encounter with Ned Goy’s works dates back to the early 1980s, when I purchased a simple, today we would say unattractive, pamphlet in an antique shop in Belgrade. O dva lirska ciklusa Momčila Nastasijevića [On the Two Lyric Cycles of Momčilo Nastasijević], a fifty-page essay published in 1969 by the Bagdala publishing house in Kruševac (and translated from English by Miroslav Nastasijević), then one of the most sophisticated publishers not only in Serbia but in all of Yugoslavia.

Curiously, the essay was first published in 1966, in the Neapolitan magazine “Annali dell’Istituto universitario orientale”, but with a different title.

I will not dwell now on the books kept in my studio in the school where I taught for years, nor do I intend to recall their fate. Just one observation: among those books was Goy’s essay on the two poetic cycles of the most mysterious Serbian poet. Some thirty years after the war, I received another copy of that essay, sent to me from London by the wife of the great Slavic scholar, Jasna Levinger Goy, with whom I collaborated while writing an article about her interesting book Out of the Siege of Sarajevo: Memoirs of a Former Yugoslav.

In his essay analysing Nastasijević’s poetry, Goy also expresses his own highly original ideas about poetry and, implicitly, about art in general. “Poetry is a living experience”, argues Goy, “an expression of truth, of the beauty that lies behind reality. Style as an isolated category exists only artificially. Rather than constituting a work, it tends to precede it. Because every true style is inseparable from the work; it is the work itself. Therefore, to speak of art as morality is to illuminate only a small part of the truth”.

I believe this essay should also be taken into consideration when analysing Goy’s other works. By arguing that Nastasijević’s style has “the compactness of a telegram”, Goy also offers us a key to understanding his own work, including the poems he continued to write, albeit less intensely, throughout his life. These poems were later collected by his wife and published posthumously in a private edition. (One of Goy’s poems has been translated into Serbo-Croatian by a friend of mine who prefers to remain anonymous.) Goy also loved drawing, and he drew so well that it seems he did not do it simply for personal pleasure.

Shortly before his death, he made an appeal to his Slavist colleagues in the former Yugoslavia. The appeal was first published in the collection of papers presented at the international conference “Interculturality and Tolerance”, held in Belgrade in 1998.

A single fragment, which I cite below, is enough to reveal the nobility of a soul that clearly saw evil in cultural and literary barriers and boundaries. “I address this appeal, hoping it is superfluous, to my Slavic colleagues, because I am concerned about the divisions all too closely linked to current events. It is a call to gather and preserve what we must save: the body of human culture in all its richness. Our task encompasses the entire literary realm. Like artists, we too are timeless. Our task is to calmly and sensitively preserve what is precious. Otherwise, we would join the ‘current of time’. So who will save what is at risk of being lost, an authentic human existence, expressed so tragically in a vital and varied, if minor, language in such a complex and contradictory human experience? If we do not do it, who will?”.

While the twenty-fifth anniversary of Ned’s death has gone unnoticed, the centenary of his birth, which occurs next year, could be a good opportunity to pay homage – in Croatia and Serbia – to the most important scholar, from the Anglo-Saxon world, of literature and translation of the works of Croatian and Serbian authors. Perhaps a conference could be organised? Or would it be better to make a documentary in Serbo-Croatian? This, however, is a question that cannot be resolved from my small balcony in Friuli, from which the gaze extends toward my native land.

Ned Dusko

1950

The Now that has me on its reach

Is gone, in a flash.

And I become a historian.

Yet still it comes back,

Driven by an over-riding rhythm,

The slow beat of a counterpoint

Like the rain continuing to splash

And irrevocably dribble.

Which, now, shall I speak of?

This or that?

Must I be my own biographer?

Write an epitaph of a defunct Now?

Oh, one could laugh,

Strangled to utter

The pain, to find a listener

To confront the minute

When the mother bows her head

To hear

And I have nought to say in it!