Indignity: reimagining life in Southeastern Europe

In a quest for truth, renowned author Lea Ypi, with her new book Indignity, embarks on a journey that carries her from the multiethnic setting of the last days of the Ottoman Empire to the rise of fascism across Europe, and the subsequent establishment of proletarian dictatorships in the East

Indignity-reimagining-life-in-Southeastern-Europe

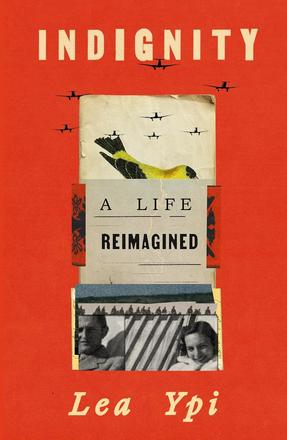

Book's cover

Through a sharp female gaze, Lea Ypi reimagines past lives of real individuals who navigated between collapsing and emerging worlds, more than often at the expense of their own freedom and dignity. Her motives are profoundly personal, yet she approaches her subjects and the historical facts with the clarity and objectivity of a mature scholar.

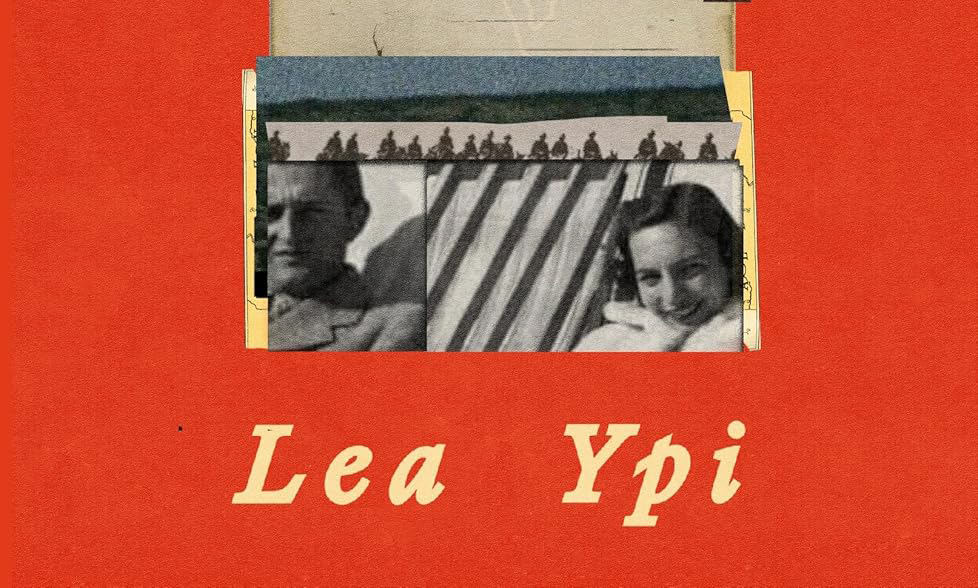

It all starts with a 1941 photograph of her grandparents, Leman and Asllan Ypi, captured vacationing in a glamorous alpine resort of Cortina, nestled in the heart of Italy’s Dolomites. Long thought lost, the photograph survived the 1947 persecution of the family by Albania’s communist regime, even though it remained sequestered in a state archive, out of the family’s reach.

In her attempts to understand who her grandmother truly was — and why she was smiling in that 1941 photograph, as the Second World War raged across Europe and Nazi Germany pressed eastward — Ypi pieces together the story by delving into archives and documentation centers from Albania to Greece, from Italy to the United Kingdom, and further across the continent.

She reconstructs cities and countries, revives realities, and captures the dynamics of everyday life in the Balkan Peninsula across shifting times with the vividness and precision of a cartographer mapping lost worlds. Thus, the historical and social background from which her characters are shaped is not a figment of her imagination but a result of the archival evidence and real-life testimonies she uncovers.

Through this book, Ypi demonstrates that she is not only a rigorous researcher and knowledgeable writer, but also an empath: she approaches her characters both with curiosity and tenderness, never intruding their privacy, yet opening a window onto the intimate worlds of girls and women who endured not only the harrowing upheavals of their times but also the suffocating weight of patriarchy embedded in the very structure of their class and society at large.

Leman, the protagonist of the story, comes from an ethnically Albanian family belonging to the landed aristocracy and administrative elite in Salonica (today’s Thessaloniki), one of the most important economic, cultural, and intellectual centers of the Ottoman Empire.

Although she reads, writes, and speaks several languages; enjoys the privileges afforded to peers of her social standing, with access to information and goods flowing from across the globe; and benefits from an education that introduces her early to the thinkers and ideals of Western Enlightenment, her freedoms are fundamentally constrained.

The choices that define her own life — whether to marry, whom to marry, whether to pursue higher education or be confined to domesticity, and the very type of life she may lead — remain largely dictated by patriarchal social norms and expectations.

Even in her attempts to defy these norms and expectations, the political reality around her takes unpredictable turns and simultaneously predetermines the limits of her choices. Can one truly exercise free will when freedom itself is absent?

This contrast underscores the limits of formal privilege: even the most educated, cosmopolitan, and well-connected young women of Leman’s socio-economic class were still denied autonomy over the most intimate and consequential aspects of their lives.

The paradox is symbolically embodied in Selma, Leman’s aunt — a strong and sympathetic character who, despite seeking liberation through self-education, was undone by the socio-political order she inhabited. Her story illustrates a crucial point: education alone, when not anchored in institutional and structural change, cannot deliver true emancipation. Instead, it risks becoming merely a false promise.

A common thread runs through authoritarian regimes across history — from the Ottoman Empire, to fascist Italy, to Hoxhaist-Stalinist Albania, as highlighted by Ypi: these are systems structured to serve a narrow elite, where individual freedom and human dignity are systematically suppressed, leaving little room for autonomy or justice.

They do not benefit women and all those who are othered or perceived as “unfitting” or vulnerable, as they reinforce the power of the strongest, often associated with male dominance. As a consequence, the structural mechanisms that uphold the regime’s authority simultaneously perpetuate inequality, making true emancipation and gender equity impossible under such conditions.

For instance, in chapter three of part two, the book uses irony to vividly expose the banality and mediocrity of such power structures, embodied in none other than Enver Hoxha himself, whose iron rule held Albania captive for forty-five years, and, like Lea Ypi’s grandfather, sent tens of thousands of innocent citizens who did not agree with Hoxha’s vision of Albania, to notorious political prisons and labor camps.

Through this passage, Ypi underscores the paltriness of power and the dissonance between appearance and reality in authoritarian contexts where under the image of polished authority lies nothing but moral rot and political incompetence: “The young man turned towards Leman but was briefly distracted by his [own] reflection in the glossy dark window dividing the veranda from the interior of the new cafe. He took off his beret and ran his fingers through the dark wavy hair. It was carefully styled upwards with a brilliantine pomade that smelled of lavender and made his hair shimmer in the evening light. She noticed his shoes, well worn but impeccably polished, but as he took a seat next to her, she could also smell raw onion on his breath, and the resulting blend of onion and lavender was so unbearable that she pulled back her chair instinctively.”

A comparable moment sets the tone at the beginning of the book, when the cause of Ibrahim Pasha’s death, Leman’s grandfather, is attributed to overindulgence in baklava — a lighthearted yet telling passage that highlights the timeless greed of high elites and the triviality that pervades their exercise of power.

Reading these stories through the voice of an Albanian author and as an Albanian woman is important because it brings forward perspectives that have long been silenced or marginalized. The history of the Balkans has mainly been narrated by outsiders, specifically, male authors or researchers who have either exoticized or viewed the region through a Western colonial gaze.

Ypi reclaims that narrative, not only by grounding it in lived experiences and historical specificity, but also by highlighting the gendered dimensions of oppression, resilience, and survival.

She reclaims silenced voices while confronting the dual erasure of coming from a small country and being a woman in it. In doing so, she transforms personal and collective memory into a universal reflection on freedom, dignity, and justice, showing how the personal and the political are inseparably connected.

Although it might carry particular significance for Albanian readers, the book remains entirely accessible to audiences far beyond Albania: no prior knowledge of Albania or the Balkans is required to grasp the book’s sharp sarcasm or its layered political, cultural, and historical realities. Ypi writes in clear, direct language, offering just enough context without ever slipping into patronization so that the local becomes universal, and the particular resonates as human.

By transforming the past into an instrument of learning, Indignity invites us to also view the contemporary political crisis and insecurities, such as the rise of nationalism and extreme-right populism, not as unique to our time, but as recurring reminders of how delicate our democratic institutions and ideals of justice and liberty truly are when they are not actively defended every day.

As Dr. Elias, the Jewish physician of the Ypi family in Salonica who personifies the human cost and the weight of twentieth-century totalitarianism(s) remarks: “We may have some problems now, because of the current crisis, and people become impatient and lose faith. But it will be resolved; we’ll sort it out just as we have done in the past, and we will all learn from our mistakes.”

In this regard, the power of imagination emerges as a radical force, enabling us to confront present challenges with insight and learn from history, to be able to envision a more just and resilient world.

Indignity is a book anchored in the past, using history as a lens to challenge the present and illuminate the choices that shape who we aspire to be today.