Brijuni, then and now

The Brijuni Islands, a small national park in the northern Adriatic, have a very unique history. Once a malaria-ridden area with inhospitable terrain, they became an important tourist destination in the 19th century thanks to Austrian entrepreneur Paul Kupelwieser. In this two-part report, we explore their history and present-day reality.

Brijuni-then-and-now

Brijuni, Croatia - Foto G. Vale

Only ten minutes of sailing separates Fažana, on the Istrian mainland, from the Brijuni Islands. Upon arrival at the main pier of the archipelago, on Veliki Brijun – the largest island, with an area of just over 5 square kilometers – you will find yourself immersed in nature, often also in silence.

Since 1983, the Brijuni Islands have been a national park, limiting the number of visitors and prohibiting the use of private vehicles. The atmosphere is relaxed, and the days pass slowly, with long walks, golf and swimming in the sea. People come here in search of a peaceful place to recharge their batteries.

This is the case with Zoran and Lavinia, Croatian tourists from Zagreb, whom we meet just north of the pier, along one of the paths winding through the trees. It is early June and the couple, like every year, is staying here for a week.

“She brought me here for the first time. She said, ‘It is a marvellous place, we have to go!’ And we have been coming every year since then, more or less at the same time”, explains Zoran.

The reasons why it is worth visiting the Brijuni Islands are obvious, says his partner Lavinia. “We are far from civilization, there is no traffic, just peace, quiet, the sounds and beauty of nature. In short, everything we really need in our stressful lives”.

In 2024, approximately 230,000 people visited the Brijuni islands, one of Croatia’s most famous national parks. But the islands have not always looked like this. Just over a century ago, the archipelago was an inhospitable area, plagued by malaria.

History

The trasformation of the Brijuni Islands will forever remain associated with the name of Paul Kupelwieser (1843-1919), an Austrian entrepreneur and steel magnate, who in 1893 purchased the islands for 75 thousand florins (today just over 800 thousand euros) with the intention of turning them into a tourist destination.

The archipelago, like the rest of Croatia, was then part of the Habsburg Monarchy, and tourism was in its infancy. Not far from the Brijuni Islands, the first hotels sprang up in Opatija, Pula and other towns on the northern Adriatic.

Railway networks, built across the empire from the 1850s onwards, enabled the wealthier classes to reach attractive seaside resorts. However, on the Brijuni Islands, the land had to be drained and malaria completely eradicated before the first tourists could be welcomed.

Paul Kupelwieser entrusted this first operation to Alojz Čufar, a Slovenian forester who radically changed the islands, especially Veliki Brijun.

“Alojz Čufar changed the topography of the island in an approach that was very modern at the time. He filled in the swamps and created hills using materials from nearby quarries”, explains Croatian architect Emil Jurcan. “The result is what we see today: a kind of English-style park, one of the first in continental Europe and in the then Habsburg Monarchy”.

The paths traced by Alojz Čufar still wind for tens of kilometers on Veliki Brijun today, passing through forests made up of thousands of trees, mostly evergreens, planted at the end of the 19th century.

Thanks also to the advice of Robert Koch, a German microbiologist and winner of the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 1905, who helped Paul Kupelwieser clean up the archipelago, malaria was eradicated within a year, and the Austrian entrepreneur was able to move on to the second phase of his investment project: building tourist infrastructure.

Tourism in the 19th century

Today, travelers arriving on Veliki Brijun are greeted by three elegant, albeit somewhat dilapidated hotels: Istra, Karmen and Neptun, a direct legacy of Kupelwieser’s work from the early 20th century.

“Kupelwieser had an entire hotel complex built in the port area, of which only three buildings remain today, having survived the bombings during World War II”, explains Emil Jurcan. “From an architectural point of view, they are interesting for two reasons: first, they display the Art Nouveau style typical of the early tourist infrastructure of Austria-Hungary, and second, the buildings were renovated and modernised in the 1930s when the island was administered by an Italian government agency”.

It was these hotels with a landscaped coastline, surrounded by parks and paths, with a heated seawater swimming pool in operation since 1913, that made the Brijuni Islands an attractive destination in Austria-Hungary at the beginning of the 20th century.

A direct night train then connected Vienna and Pula, bringing the cream of Austrian society to the then military port of the empire and, after a short boat trip, arriving at their destination early in the morning.

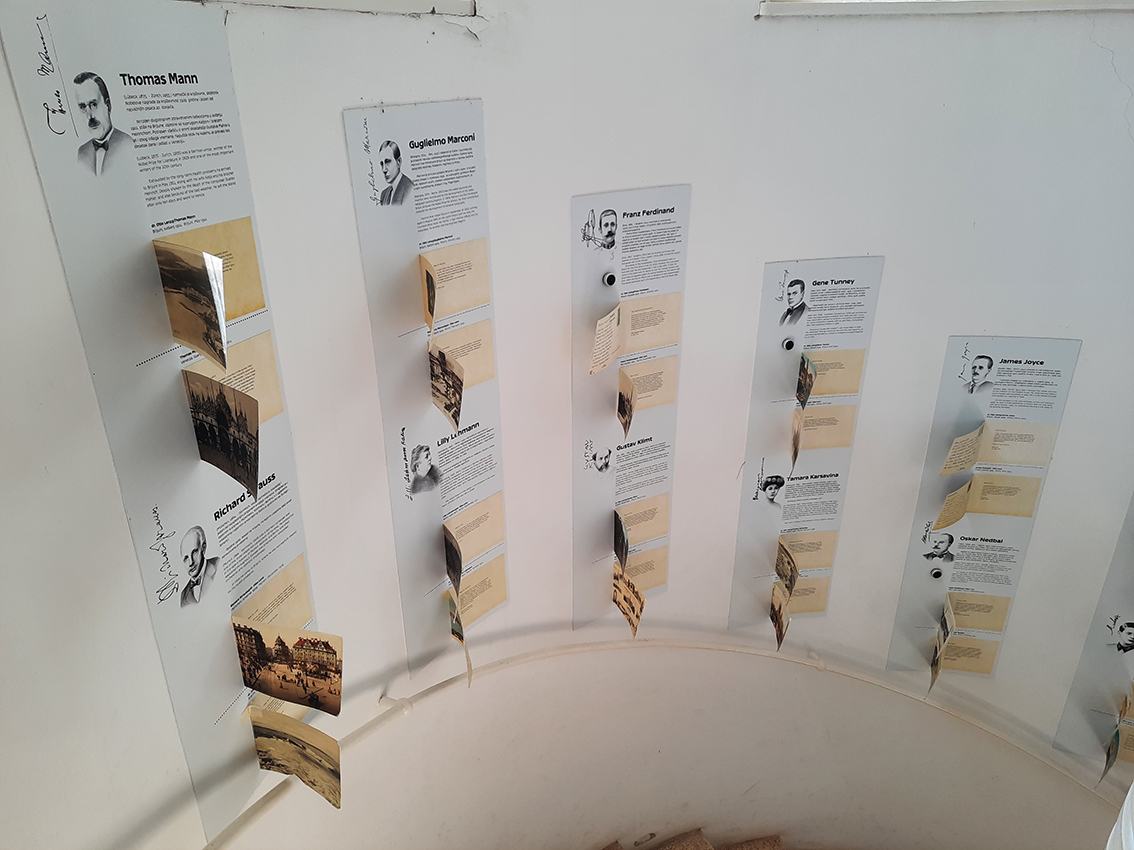

Opposite the Neptun Hotel, in what was once the home of Otto Lenz (who was a doctor on the island of Veliki Brijuni from 1903 to 1938), now a museum, we find clear testimony to the type of visitors who came to the islands at the beginning of the 20th century.

On the wall next to the spiral staircase leading to Lenz’s apartment hang dozens of letters signed by as many famous visitors to Brijuni: Thomas Mann, Richard Strauss, Guglielmo Marconi, Lilli Lehmann, Franz Ferdinand, Gustav Klimt, James Joyce… In short, the transformation that Kupelwieser desired marked a true golden age for the archipelago.

The Brijuni Islands today, thanks to European projects

“Veliki Brijun is what it is today thanks to the work of Paul Kupelwieser, who transformed this place”, confirms Marina Giachin Paoletić, project manager at the National Park.

Paul Kupelwieser’s summer house, in the center of the island, will soon be converted into a museum. This is not the only project aimed at enriching the archipelago’s tourist offer. From 2016 to 2021, Marina Giachin Paoletić led the "Novo ruho Brijuna" , one of the most important projects implemented on the islands to date.

Financed by the European Regional Development Fund and a Croatian public fund, the project entailed a series of modernisation activities on the islands, totaling almost six million euros.

For example, tourist trains were purchased to tour the island, an information point was created near the pier on Veliki Brijun, and most importantly, the island of Mali Brijun was opened to the public.

“Seven military barracks in the bay of St. Nicholas on Mali Brijun have been renovated and repurposed for educational and research purposes. In the summer of 2022, the island was opened to these groups, and then for day trips. This was possible thanks to another activity financed as part of the project, namely the design and construction of the catamaran ‘Mali Brijun’ which shuttles between Fažana and Mali Brijun”, concludes Marina Giachin Paoletić.

From Kupelwieser to Tito

Paul Kupelwieser’s story, unfortunately, does not have a happy ending. The Austrian entrepreneur died in Vienna in 1919 at the age of 77. Although he planned to be buried with his loved ones in the family mausoleum on Veliki Brijuni, his remains are in the Austrian capital, far from his wife and son, who rest on the archipelago.

World War I ruined Kupelwieser’s plans, abruptly ending the golden age of the tourist complex. However, anyone walking around Veliki Brijuni today cannot help but be fascinated by the work of the Austrian entrepreneur. Among the carefully designed landscapes and exotic animals brought to the island during Kupelwieser’s time, the traveler feels as if he is somewhere else.

“A colony of the Habsburg Empire”, says Iranian artist and writer Behzad Khosravi Noori, one of the authors of a documentary about the Brijuni Islands.

“My interpretation is that Paul Kupelwieser wanted to show the Habsburg Empire what it means to have a colony, because without exotic countries you cannot really call yourself an empire. Without colonies, there is no empire. So, Brijuni is a utopia, a theater of an exotic country, which otherwise would not exist in Europe”, explains Behzad Khosravi Noori.

The work of the Iranian artist is a kind of necromancy: two historical figures, long deceased, narrate about their “own” archipelago in front of the camera. Kupelwieser and Josip Broz Tito. After the Italian occupation, the Brijuni Islands were heavily bombed during World War II, and after the end of the conflict, assigned to socialist Yugoslavia becoming the summer residence of Marshal Tito, who spent four to six months a year on the archipelago.

At that time, historians explain, this small archipelago was actually the second capital of Yugoslavia, after Belgrade. But we will talk about that in the next chapter.

Read more: Brijuni, the second capital of Yugoslavia

This article is published as part of the Cohesion4Climate project, co-funded by the European Union. The EU is in no way responsible for the information or views expressed within the project; the sole responsibility lies with OBCT.